ASU offers first-time course on American Indian community planning

A group of nearly 50 undergraduate and graduate students participated in an accelerated, interdisciplinary course called American Indian Community Planning, offered for the first time at ASU this spring. ASU professors Michelle Hale, from the American Indian Studies program, and David Pijawka, from the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, jointly delivered the course.

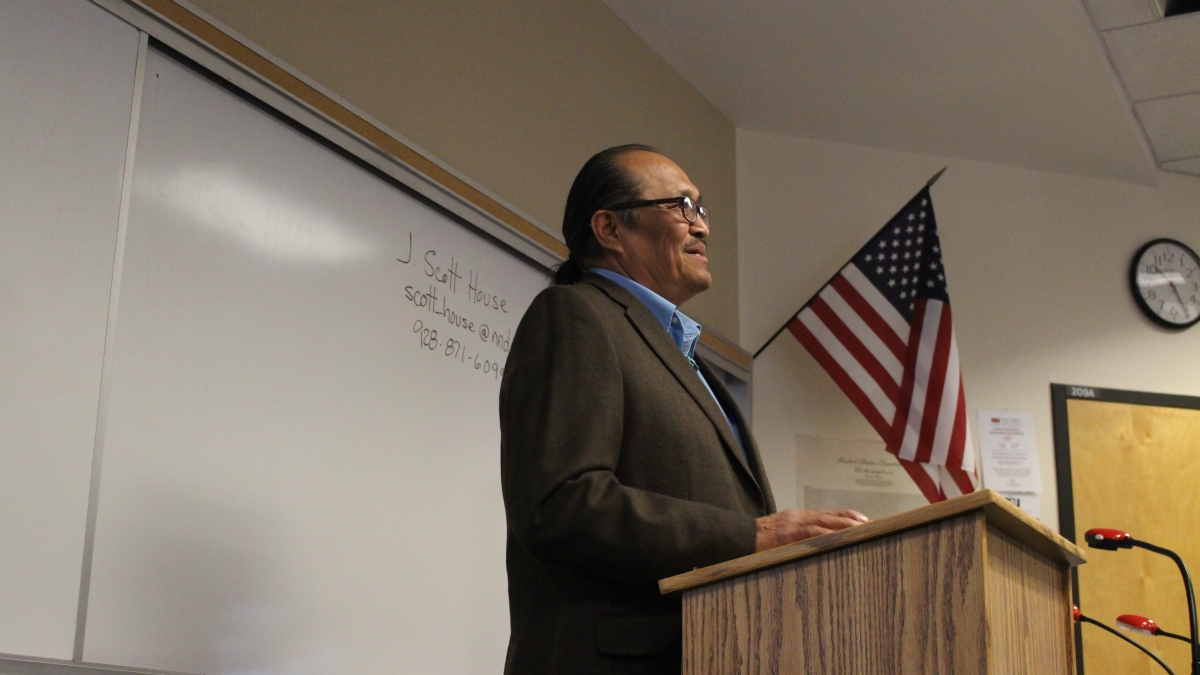

The new course, which took place over two, weekend-long workshops, provided students a chance to learn firsthand from ASU scholars who specialize in American Indian culture, law, governance and planning. Private and public sector professionals working on planning issues in American Indian communities also presented on their specific areas of expertise.

Pijawka said he was pleased to see such a large turnout for the first-time course. “Within a few days of placing the posting for the course, we had close to 50 students. I almost fell off my chair.”

Building a blueprint for land use planning

According to Pijawka, his interest in offering the course stemmed largely from working with tribal nations. He recently prepared a strategic plan submitted to the Navajo Nation that, if adopted, will provide a blueprint for the nation’s comprehensive land use planning. Pijawka said that experience revealed a need for a course tailored to Native American communities.

“So many tribes do not have planning departments” said Pijawka. “Often, tribes don’t have their own expertise. They don’t have certified or professional planners.”

James Gardner, who served as a teaching assistant for American Indian Community Planning, was also involved in the Navajo Nation project. He said feedback from Navajo representatives provided a real impetus to develop the Native American community planning course.

“Every time we had a meeting with representatives from the Navajo Nation, they would say, ‘When are you going to send back people to work on planning here?'” Gardner said. “They wanted their own people to come back and work on urban planning.”

Hale, an assistant professor of American Indian Studies and a member of the Navajo Nation, said that in many instances, existing infrastructure in Indian country could be improved so that citizens have reliable access to running water, electricity and housing.

According to Hale, Native communities could benefit from infrastructure development that considers the long term.

“Often, immediate needs consume federal dollars allocated for transportation, roads and housing,” said Hale. “Indian Nations get busy putting those dollars to work to meet that immediate need and don't always have the time or opportunity to plan for the next 20 or 50 years out.”

Tribal context adds complexity

Hale said American Indian Community Planning aimed to expose students to the complexities that planning in Indian Nations can entail.

“In a tribal setting, the process and politics that go hand-in-hand with a planning process are unique, due to the special legal and political relationship that Indian Nations have with the United States government,” Hale said. “That relationship impacts funding, decision-making and land access because often, tribes must work in tandem with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.”

Stephanie Watney, a master’s candidate in urban and environmental planning and a First Nations Canadian, said the course was a good chance to get involved on issues affecting Native communities.

“The reason I moved to Arizona from Canada was because of the large Native populations,” said Watney. “I wanted to study the initiatives in Arizona compared with Canada. This course was a great opportunity for me to hear from and engage in conversations about real 'change' in Native communities.”

As part of the course, students teamed up and prepared a practical proposal on a specific planning issue affecting a Native community. Watney’s team prepared a proposal for a Boys and Girls Club on the Hopi Tribe’s reservation. Student teams were mixed – containing grad students and undergrads from both American Indian studies and urban planning.

Watney said the partnership between American Indian studies students and planning students was unique, and she saw the collaboration as a useful way to learn.

“I feel it was a good opportunity for planners to become less naive, and for American Indian studies students to begin to become familiar with tools that can assist in developing their communities,” said Watney.

A unique learning opportunity

Gardner agreed that for many urban planning students, the course was a chance to expand their horizons.

“In urban planning, we typically speak to urban issues like blight, but we tend to not give as much attention to rural communities.”

According to Gardner, many planning students enrolled in the course because the topic was something on which few had any real knowledge.

Pijawka said offering the course this spring in a compacted form served to gauge interest level. He hopes to see the topic developed into a broader program in the future.

“I’ve argued for a long time to have a professional planning program focused on planning in American Indian communities,” said Pijawka.

Following the success of their trial run with the course, Pijawka and Hale are currently discussing plans to offer American Indian Community Planning again next spring.

The School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning and the American Indian Studies program are academic units in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Wynne Mancini, Wynne.Mancini@asu.edu

School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning