Women's, African-American history converge in Civil War-era cabin

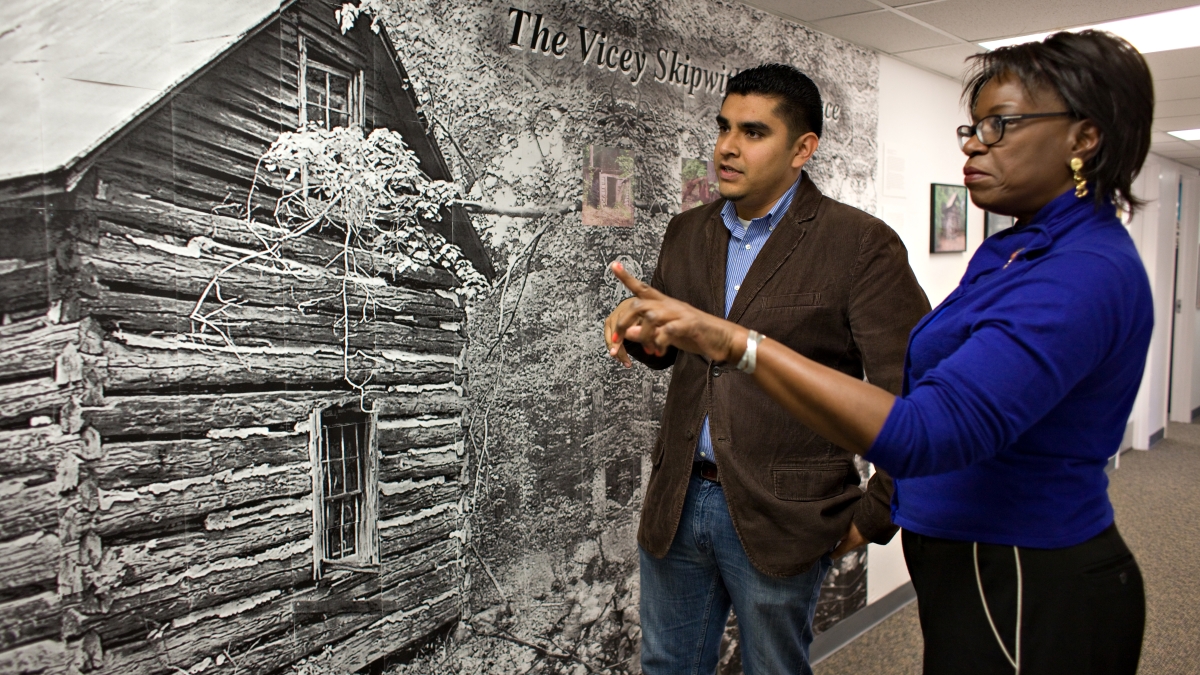

A photographic mural of a Reconstruction-era Virginia log cabin dominates the hallway leading to African and African American Studies faculty offices in the School of Social Transformation, within the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, in Wilson Hall. From afar it reads as one seamless piece of art, beckoning visitors to step into another place and time. But a closer look reveals more than 200 small prints, meticulously pieced together to create the 15-by-7 foot scene.

The composition’s format parallels the historical detective work that ASU’s Angelita Reyes, professor of African and African-American studies and English, has done to give context to the cabin, which stands in the woods of a rural community in Mecklenburg County, Va., and to fit together a biographical voice for her ancestors and other African-American families who built lives on former plantation lands after Emancipation.

Reyes says the project began as a family effort to qualify the Civil War-era cabin for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register; both were achieved in 2007.

“The historic log cabin site is named after my great-grandfather, Patrick Robert ‘Parker’ Sydnor,” she explains. “Born in 1854, he was a stone mason and successful tombstone carver and he lived in the cabin intermittently during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.”

But for Reyes the project became much more. Her interest expanded beyond her immediate family’s connection to the cabin when her research into the public archives “introduced” her to a woman named Vicey Skipwith (1856–1936), who purchased in 1888 – just 11 years after the military end of Reconstruction – this log cabin and six acres on the same land that Vicey’s parents had been enslaved.

“Skipwith became a wage laborer on the Prestwould Plantation after the Civil War, with census records noting her skills as a cook,” Reyes says. “She paid $62 for her six and one-fifth acres of land. She also paid 50 cents in taxes the following year. Sixty-two dollars in 1888 is the approximate equivalent of $1,500 in today's economy – still a substantial amount of money.

“Vicey was among the thousands of newly freed people who established themselves in communities and purchased land throughout Virginia. Regardless of the quantity of acres, each purchase was a truly remarkable achievement,” Reyes observes. “I felt compelled to search for the voice of this spirited, non-literate woman, whose life spanned the last nine years of slavery, the Civil War, Emancipation, Reconstruction, the beginnings of the Jim Crow South, and the Great Depression in 1930s New York City.”

Reyes, who had grown up living in California, Honduras and New York City, but spent many summers on her grandmother’s farm in Virginia, began engaging in “memory telling” with some of the county’s older residents, whose knowledge of post-Civil War life and stories had been passed down from their own parents and grandparents. She scoured public records, U.S. Census databases, and Mecklenburg County Slave Schedules.

“When I was not in Virginia doing field work, I immersed myself in reading about women and slavery, Virginia history, vernacular architecture, navigable waterways, material culture, and the Civil War,” Reyes says. “And every time I went back, I introduced myself to new people, especially the elderly. They were also ‘libraries.’ As an African proverb tells us, when the elders die, libraries are gone. And so, I often went to the elders – black and white – in order to hear them talk through memory-telling.

“Because the church continues to be an important African-American social institution, I attended different churches on the Sundays of my field trips in order to connect to the elders and their informational stories,” she notes. “I needed to know about the generations of people who had their home places where Vicey Skipwith had lived. I talked with local people, trying to get access to the cultural past through the voices of the present.”

Combining these resources with greater truths emanating from knowledge of gender roles, emancipation, the rights of citizenship, and land ownership, Reyes says she was able “to fill in the spaces between documented history and collective memory,” crafting a story that gives rich context to the cabin and a glimpse into the inner lives and ambitions of Vicey Skipwith and her contemporaries.

In doing so, Reyes has ensured that the Patrick Robert Sydnor log cabin site functions as a material artifact of slavery and as an unconventional text for autobiographical truths beyond slavery. (Read a captivating account of Reyes' research at Common-Place.org, in a piece titled “Not Even Past: Six Acres and a Mule or Searching for Vicey Skipwith.”)

When the Sydnor Cabin was entered into the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register in 2007, it was with a designation of “local level of significance.” Reyes received official confirmation last month that additional documentation she provided about the property and Parker Sydnor’s work as a craftsman of grave markers had moved the Parker Sydnor Cabin to a level of “statewide significance.”

The state evaluation committee noted that Virginia “has very little documentation of non-white tombstone carvers, and the fact that Sydnor is a known African American carver with an associated and locally-sited body of work is very important.”

At ASU, Reyes teaches courses on women and gender in African and African-American Diasporas in the School of Social Transformation, and on material culture and cross-cultural studies in the Department of English, in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. With innovative research methodologies, her edited books and essays cover a range of topics that focus on women and public history, gender and sexuality, migrating subjects, and visualizing slavery in the Atlantic World. Her current book project focuses on symbolic watersheds and African-American oral narratives in Virginia.

One university in many places

Reyes’s research in Mecklenburg County turned up not only an Arizona connection to this project, but a genealogical and historical relationship to Arizona State University. During the course of her research, Reyes has met two brothers, Brad Sydnor and Doug Sydnor, who are architects in Scottsdale, Arizona. Their father, the late Reginald G. Sydnor, was the architect who designed the Hiram Bradford Farmer Education Building (1960) at ASU.

“We discovered that the Sydnor brothers and I are descendants of a shared antebellum Sydnor lineage from Virginia,” explains Reyes. “A descendant of an enslaved Sydnor and Anglo descendants of the same collateral Sydnor slaveholder have crossed historical bridges and are now in collaboration on this Civil War-era project in Virginia. It’s exciting to be working to create a really new sense of place – one that will build new bridges of unity across cultures and shared history.”