From Antarctica to Arizona, professor studies desert ecosystems

For many people, the word “desert” conjures up an image of vast stretches of barren sand. Those who live in the Sonoran Desert know that desert ecosystems are much more diverse than that. But how many of us connect “desert” with “Antarctica?”

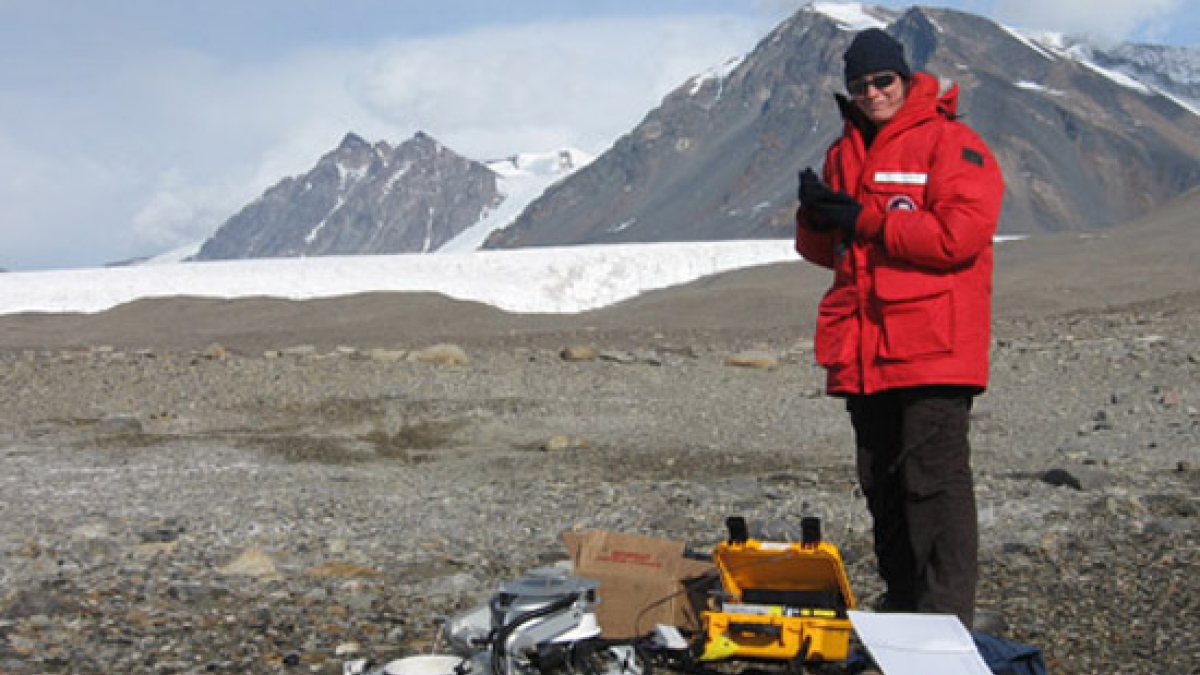

Becky Ball knows that whether you’re in one of the coldest places on the planet, or one of the hottest, you can be in a desert. It’s the lack of precipitation, not the temperature, that defines the area as a desert. Ball’s research has taken her to Antarctica and to Arizona State University’s West campus, where she is an assistant professor in ASU’s New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences.

Ball is interested in trying to decipher how changes to the global environment affect, and will continue to affect, ecosystems including deserts. For the past four years she has spent approximately two months from early December to early February at McMurdo Station, one of three U.S. research bases in Antarctica, experiencing 24 hours of daily sunlight and temperatures averaging 0 degrees Celsius (32 Fahrenheit).

Ball’s research focuses on soils. She has worked not only with desert environments but also temperate deciduous forests in the Southeastern United States as well as agricultural systems.

“The overall goal of my research is to improve our understanding of the biologic, geologic and chemical processes that take place in soils,” Ball said. “I want to contribute to improved predictions of how these processes will be affected by global change, by working to understand not just what happens, but how it happens.”

Ball literally gets her hands dirty examining the process known as nutrient cycling. The movements of nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon are some of the most important processes that occur in ecosystems, she said.

“The cycling of these nutrients relies on the plants, animals and microbes living in the ecosystem, as well as geology, chemistry and climate,” Ball said. “If organisms, climate and chemistry of the environment change, so will nutrient cycling. This change in turn affects the organisms living there. For example, too much nitrogen can be poisonous for soil animals.”

Roger Berger, director of New College’s Division of Mathematical and Natural Sciences (MNS), is pleased to have added a scientist with Ball’s knowledge and skill set to the faculty.

“Professor Ball’s studies of hot and cold deserts provide fascinating new research opportunities for our science majors, and her expertise in soil ecology and soil science will support our curriculum in environmental science,” Berger said.

MNS offers an environmental sciences concentration within it bachelor’s degree program in life sciences. The concentration prepares students for careers in both the public and private sectors, in areas such as environmental consulting, environmental remediation, and natural resource management. Graduates also may choose to enter graduate programs in environmental science or a related discipline. Future plans call for New College to develop a full major in environmental sciences, with the Arizona Board of Regents having granted the college permission to do so.

For her part, Ball is pleased to have relocated to the heat of the Sonoran Desert. “Even though I spend time in Antarctica, I actually prefer hot weather,” she said. Ball earned her Ph.D. in ecology from the University of Georgia in 2007 and then spent three years as a postdoctoral research associate at Dartmouth College as part of the McMurdo Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) Program in Antarctica.

Ball said her “typical” day in Antarctica can vary greatly. Her field work takes place in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, which receive even less precipitation than the Sonoran Desert. “On any given day I might be hiking from the field camp to sites where I’ll spend all day collecting samples, I might be taking a helicopter to distant sites to work on experiments, or I might be working from the field camp to make measurements with machinery,” she said. “I do some 24-hour projects, where I go on intermittent sleep/work cycles.”

According to Ball, climate change is the primary threat to the Antarctic ecosystem.

“Polar systems are very sensitive to small changes in temperature,” she said. “The Dry Valleys are a desert, but there’s actually quite a bit of water stored there in the form of ice. Warmer air temperatures will lead to more melting, which means the extremely dry desert ecosystem could be suddenly very wet. We observe these changes by monitoring the soil ecosystem during particular warm weather events or over natural gradients of climate, and we also simulate these differences in a controlled manner.”

Threats to ecosystems vary around the planet, Ball said, and can include such trends as desertification, invasive species, pollution, and deforestation. “These all come down to one factor: human decisions. I think that, rather than directing our attention to just one threat, we need to take into consideration that everything we do has an impact on ecosystems, and be more careful in all aspects of our decision making,” she said.

The fact that Ball now is also studying the deserts of Arizona will benefit New College students and the state as a whole, according to Berger.

“Her studies support ASU’s commitment to ‘Leveraging Our Place’ and will allow local issues to inform student learning and shape faculty research,” he said.