A monumental task: new signs for Arizona sites

Next time you visit Tuzigoot, Montezuma’s Castle and Well, Sunset Crater or Wupatki, you might see some brand-new signs describing the history of the area and the variety of plant life.

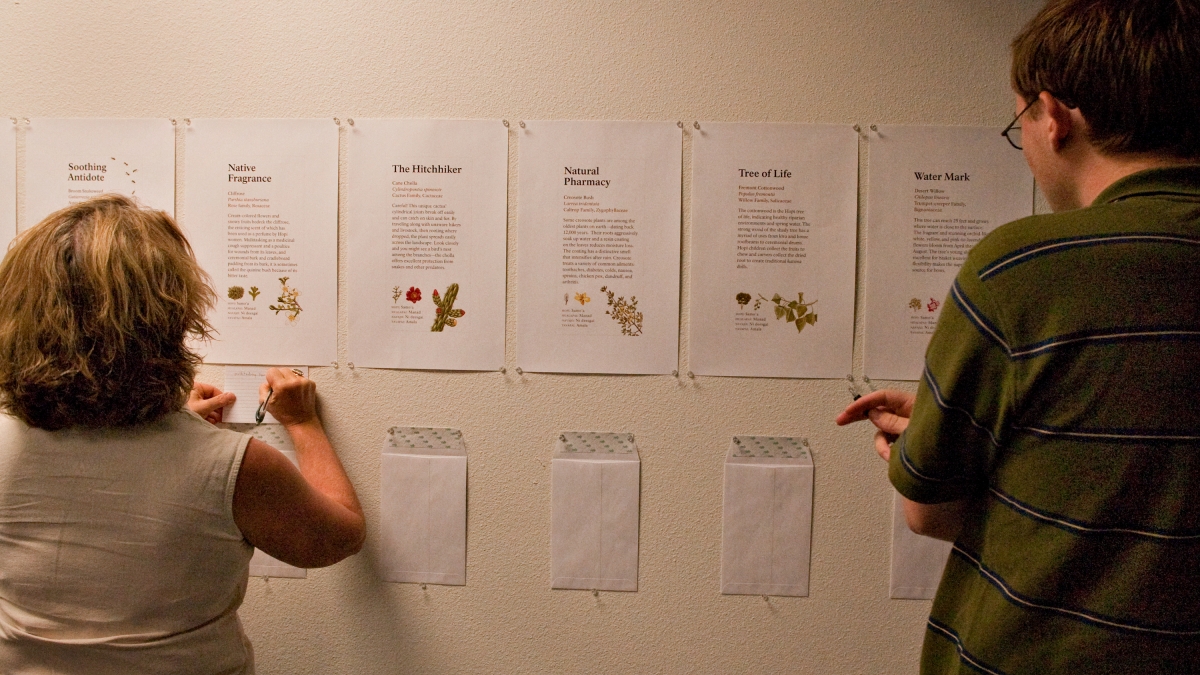

Take a close look at them – the signs (due to be completed by December and installed at a later date) are the product of many hours of work and study by ASU graduate and undergraduate students and faculty.

The project began last February when Nancy Dallett, an academic associate in the public history program, received a grant from the National Park Service to develop new ethnobotanical and interpretative signs for the five Arizona national monuments, which are clustered near Flagstaff.

The new signs, which will replace ones dating back to the 1980s, take a new tack, Dallett said. “They’ve never developed signage to take into account that people visit the monuments in a certain way.

“The current signage at the national monuments is usually so specific to each park that it rarely gives visitors the sense of relationships among the people who built and lived in these places. We’re trying to stitch them back together in the visitor’s imagination so they can get a sense of the myriad of building types, pottery, trade, agriculture, and cultures that inhabited the area circa 1100-1450. We’ll have a map at the beginning to show the relationship and location of the parks.”

Each site will have numerous signs. The ASU team created 102 in all, including 34 6-by-12-inch ethnobotanical signs, with illustrations by Las Vegas artist Brian Wignall, and 58 24-by-36-inch interpretative signs.

Over the past months, the team of six researchers and writers from the public history and scholarly publishing programs worked with four design students, under the guidance of Al Sanft, associate professor of visual communication, to create prototypes and revise them.

It was not an easy task. The students first had to learn about the monuments’ history and culture and their significance to Native Americans, then write text to tell the story in a few words. For the interpretative signs, they also had to choose appropriate illustrations, write headlines, and design the signs for easy reading.

Dallett brought in numerous consultants, including archeologists, ethnobotanists, a geographer and a geologist, to advise the students, and tribal cultural preservation officers also worked with them.

“We toured Montezuma’s Well with a Hopi medicine woman,” said Amy Long, a student in the public history and scholarly publishing graduate program. “One of the great things about the project is that it has been so collaborative,” she added. “All those sites have a multiplicity of meanings.”

The project also gave the students a chance to learn more about their state.

“Most of us had never been to any of these sites,” Long said. “We were able to explore them with park rangers.”

For the students, it was a rare assignment.

“I think it's safe to say this project has been unique – how many times do you get the opportunity to gather volumes and volumes of information and boil it down to a concise story that thousands of visitors will see? We got the opportunity to tell the story of the national parks in our own words, and that's definitely a first for me,” said Megan Keough, also a student in the public history and scholarly publishing graduate program.

Emily Jacobson, who also is working on her master’s in public history and scholarly publishing, commented, “This is definitely a unique project. As a graduate student, I feel lucky to be involved in something that will define national sites for years.”

“This is absolutely the most unique project I have ever worked on,” said Leah Harrison, a fellow graduate student in public history and scholarly publishing. “The breadth of the research required, the number of experts we consulted, and the variety of skills necessary to complete the work have made this a one-of-a-kind experience.

“We got to work with a number of people--from a Hopi medicine woman to a cultural geographer--these are experiences we likely won't have the opportunity to repeat.”

Dallett, who has researched and written about national parks and monuments as diverse as Hubbell Trading Post, Governors Island, Ellis Island and Organ Pipe, said the project has been an ideal one for students of public history because “it is about synthesizing a tremendous amount of information from various disciplines (archeology, geology, environmental sciences, natural history, cultural history, National Park Service history, ethnobotany, Native American knowledge) and making it accessible, interesting and engaging for the general public.

“This is about telling stories that help people to imagine change over time, the migration of people, the built environment, mythology, creation stories, geologic time, land management issues, and the impact of time and people on archeological sites.

“This is an ideal project for the scholarly publishing students because it is about writing and editing and bringing research to the public,” she added.

“And, it’s an ideal project for the design students because, while there are constraints on the design imposed by the National Park Service, there is plenty of room to be inventive, aesthetically pleasing, and to find a way for design to support the ideas we want to convey.”

Keough said she enjoyed the project because “the opportunity to work on something so tangible and permanent, that so many people will see for such a long time, has been exciting to say the least. I've also enjoyed visiting the sites with our experts and trying to incorporate all of their stories into one big narrative.”

Jacobson’s favorite part was “tinkering with words and taking huge amounts of research and determining the central argument/essential facts the public needs to know.”

For Harrison, the best part of the experience was “working with such a phenomenal team of individuals. Each person on our team has contributed and we have all learned from each other. Also, I have particularly loved learning how to organize and execute a project of this magnitude.”

Other students participating were Kim Engel-Pearson, Kendra Roberts, Raymond Holling, Jill Petticrew, Andrew McCarthy and Kara Zichittella.